SpatialBench: Can Agents Analyze Real-World Spatial Biology Data?

146 verifiable problems spanning 5 spatial platforms and 7 task categories

Agents for biology are stuck in the “demo-to-deployment” gap. They can look impressive in curated examples, but without realistic, verifiable benchmarks, it’s hard to tell if we’re making progress or building toys .

This gap is starting to matter. Spatial assays (and increasingly every modern measurement modality) generate outputs that are too large, too irregular, and too context-dependent for most labs to analyze without computational specialists. The promise of agents is clear: point them at raw data, ask scientific questions in plain language, and compress weeks of analysis into hours. But looking right isn’t the same as being right - especially when results guide expensive and time intensive experiments.

Software engineering arguably went through this phase already. Frameworks like SWE-bench exposed how bad models were at real programming tasks and gave everyone a number to climb. Progress in biology needs something similar: built from real workflows, grounded in real datasets, and graded by verifiable outcomes instead of vibes.

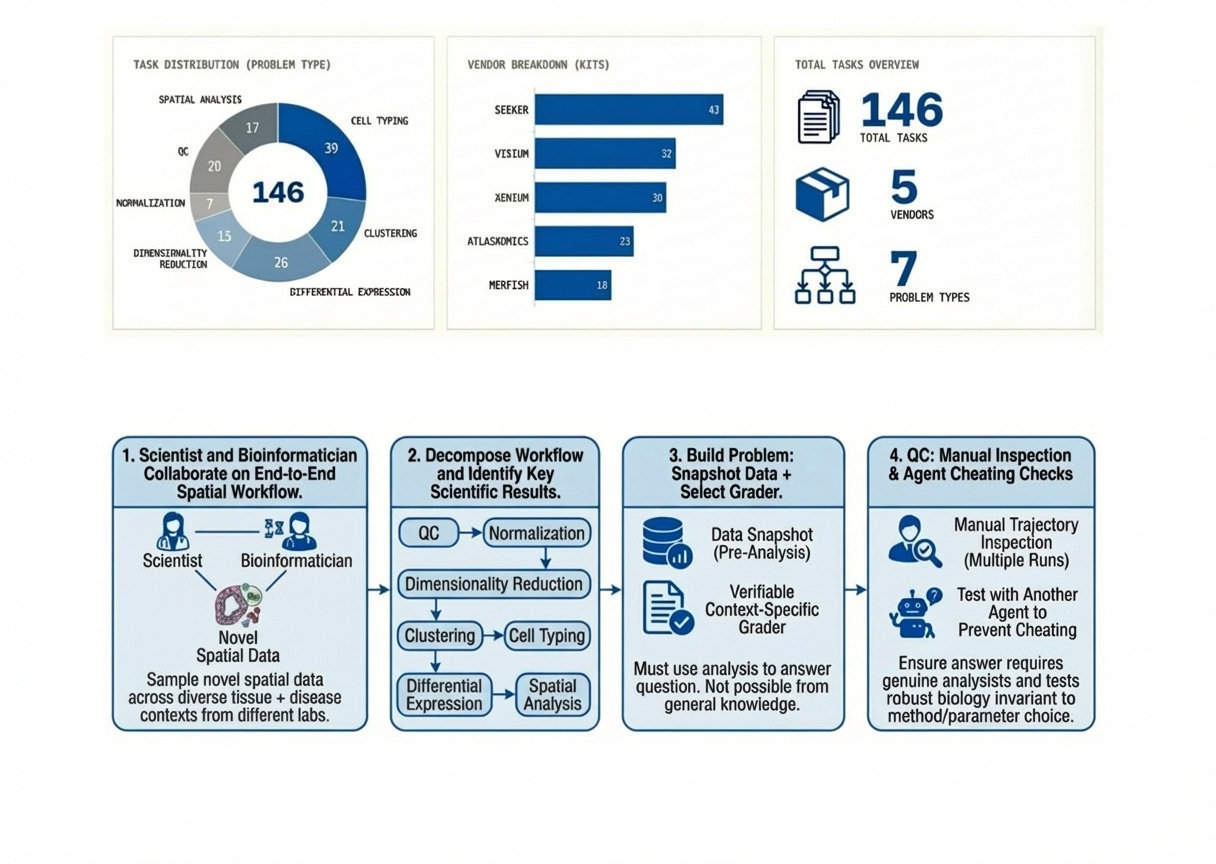

Here we introduce SpatialBench (read the paper), a suite of spatial biology analysis problems designed to recreate the work scientists actually do - inspect messy images and count matrices, write and run code, reason scientifically and recover concrete biological results.

SpatialBench approximates real analysis work

Current biology evaluations largely reward textbook knowledge, but real analysis involves empirical interaction with data to produce answers. SpatialBench is a suite of 146 verifiable problems drawn from real spatial analysis workflows, spanning five platforms (Vizgen MERFISH, Takara Seeker, 10x Visium, 10x Xenium, Atlasxomics DBIT-seq) and seven task categories (QC, normalization, dimensionality reduction, clustering, cell typing, differential expression, and spatial analysis).

Each problem is a snapshot of an analysis workspace captured right before a decision point: typically an AnnData object plus any associated files, images, or outputs from earlier steps. The tests probe for durable biology, robust to survive reasonable choices of algorithm, library, or hyperparameters. We pressure-tested each for shortcuts: inspecting logs, adversarial prompts and removing anything solvable by pattern-matching or leaning on general scientific knowledge instead of actual analysis. Find concrete examples in the paper supplements.

Agents aren’t quite there yet

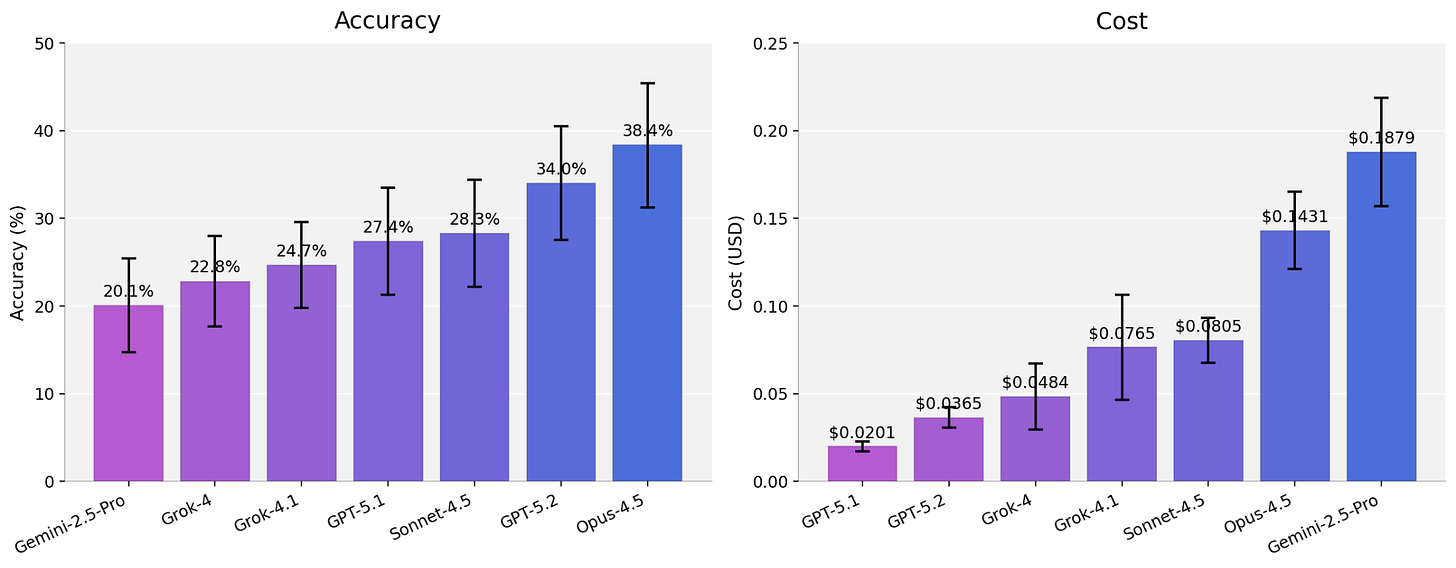

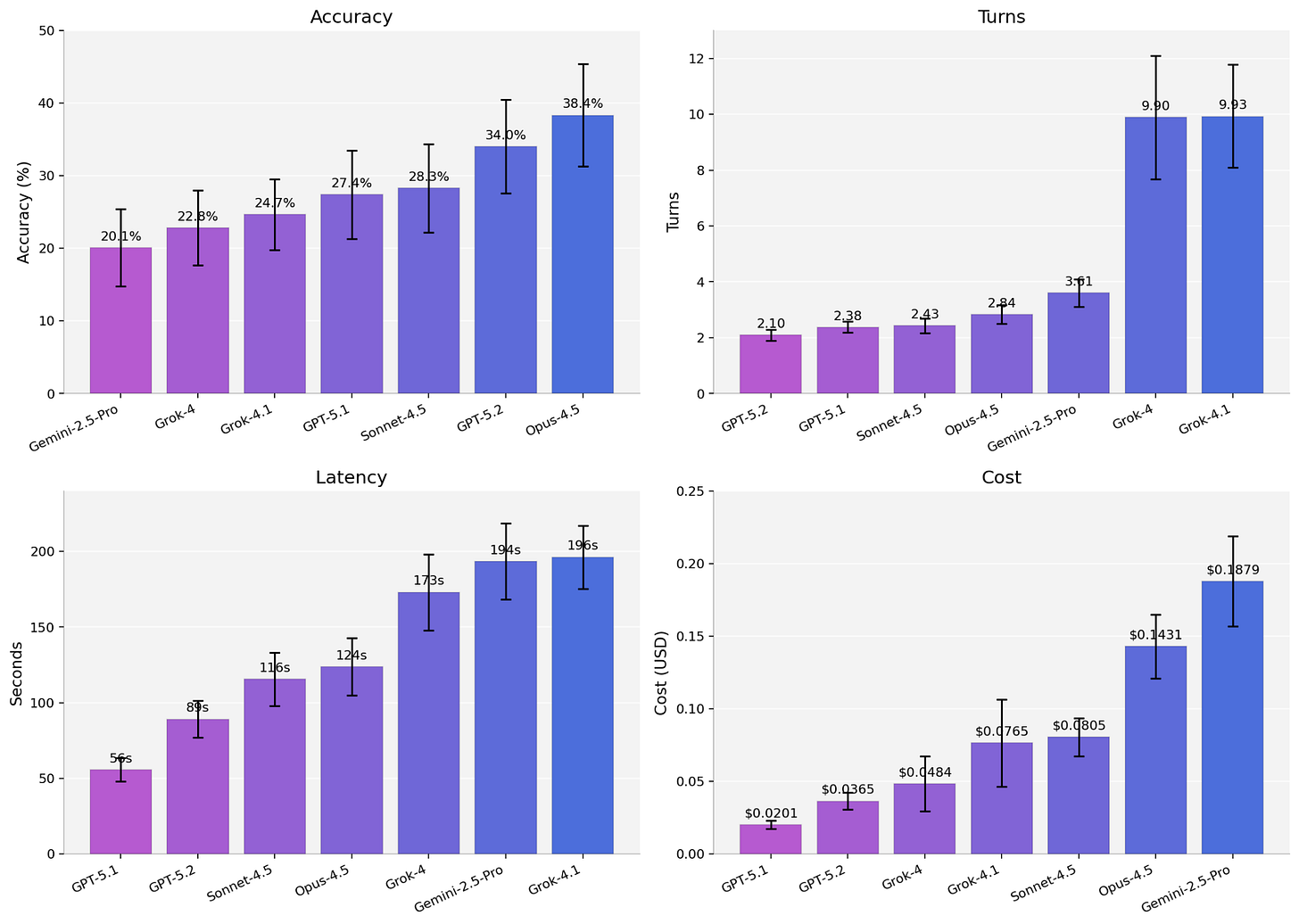

Across the full benchmark, base-model accuracy sits between 20-38% depending on the model family, with the usual tradeoffs between accuracy, latency, and cost.

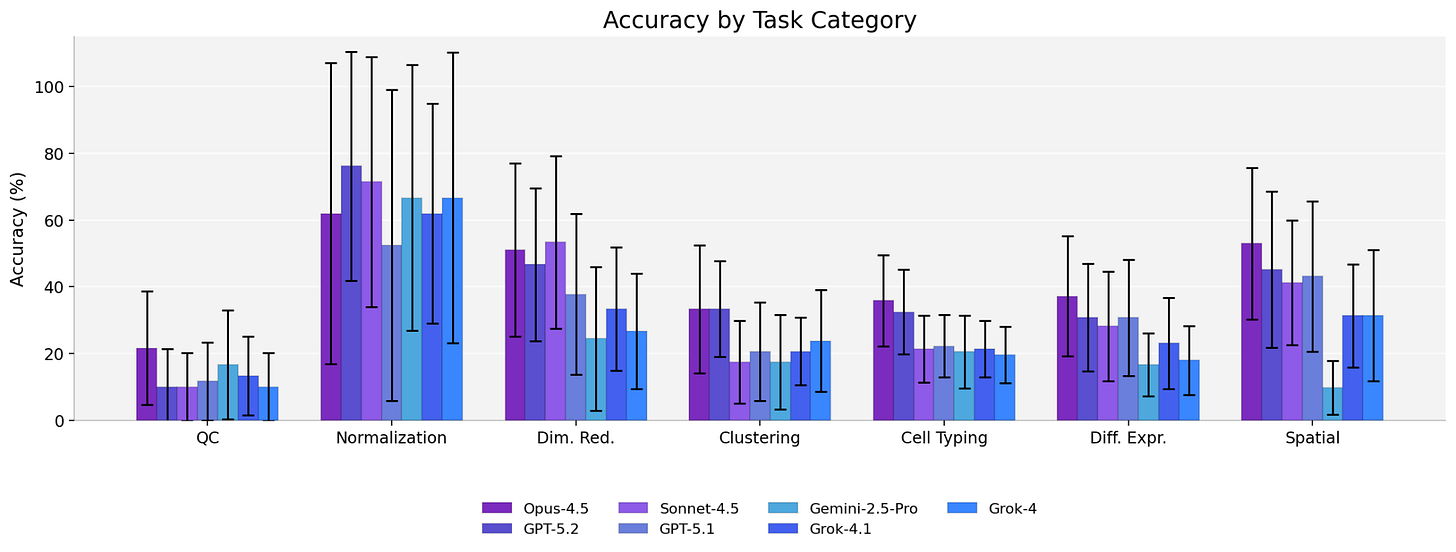

But the aggregate numbers hide detail. Stratification reveals clear model-specific variation over tasks and platforms. Some model families collapse on specific task types while others swing 15 to 20 points depending on the class of spatial technology.

Spatial biology is of course a collection of many distinct technology types and constituent steps, each with its own artifacts and conventions obscured in point estimates of accuracy. Deliberate engineering will be needed to improve across each covariate.

Harnesses are more than “glue code”

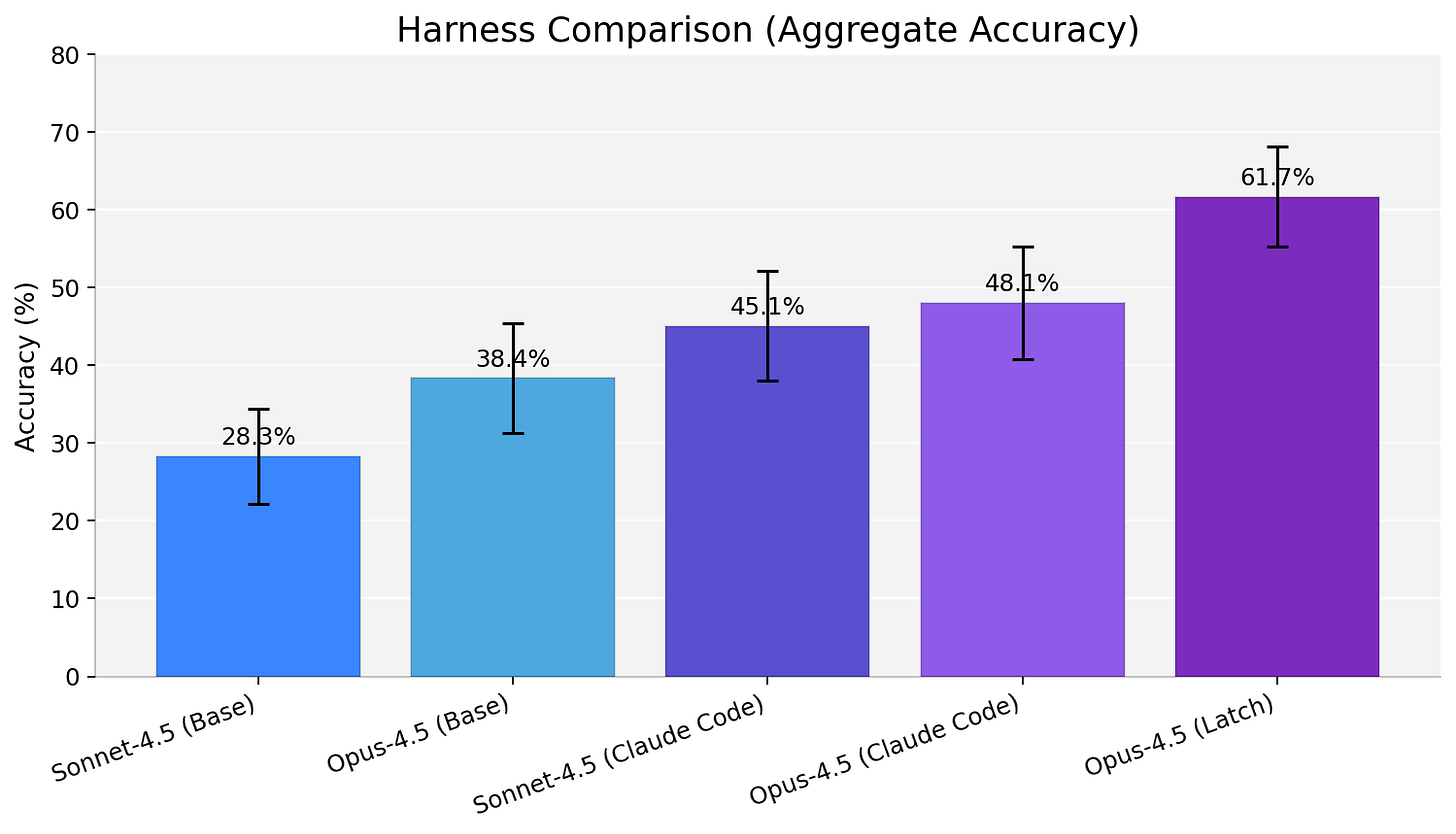

Interestingly, harness design moved outcomes as much as swapping the base model. We ran Opus-4.5 under multiple execution ‘wrappers’ - LatchBio, Claude Code and a slightly modified mini-swe-agent - and saw dramatic variation.

Our results suggest we should start treating harnesses as first class objects in engineering and benchmarking efforts. The tools, prompts, and control flow around a model are as important as the model itself.

Agent trajectories reveal distinct problem solving strategies

Manual inspection of agent trajectories - the sequence of reasoning traces, tool calls, logs from an eval session - was perhaps the most informative part of the project. This data provides mechanistic explanations for performance differences. We could pick out distinct failure modes: models burning steps on formatting with no forward progress; using general QC thresholds that don’t hold for spatial data. Some models were able to ‘productively explore’ (inspect, compute, refine, make some forward progress) while others thrashed (same failed attempt on repeat, often forever). There are many examples of these in the paper.

Limitations

Verifiability comes with tradeoffs. Nuance is lost trying to draw deterministic lines around messy real world examples. Snapshots of single steps aren’t full workflows: real analysis is longer-horizon and iterative. But measuring step-level chunks with reliability is but a step towards automating truly long time horizon tasks. More on this soon.

Where this is all going

SpatialBench is a first contribution towards a broader family of benchmarks spanning major biological modalities. We view benchmarks as evolving formalizations of tacit scientist behavior and analysis workflows. They guide test-driven development of agent systems through model training and harness engineering that will eventually automate much of what we consider to be computational biology.

2026 will be a big year for agents in biology.

Read the paper. Check out data + code. Play with some examples.

It's interesting how this benchmark could really change the pacet of progress. How do you see it impacting broader AI developpement, beyond just biology? Brilliant insight!